Not all fierce-looking dinosaurs like T rex packed strong bites, study reveals

A comprehensive new analysis of the bite forces of 18 species of dinosaurs has revealed that, despite their size, several of the giant prehistoric predators packed much weaker bites than previously thought.

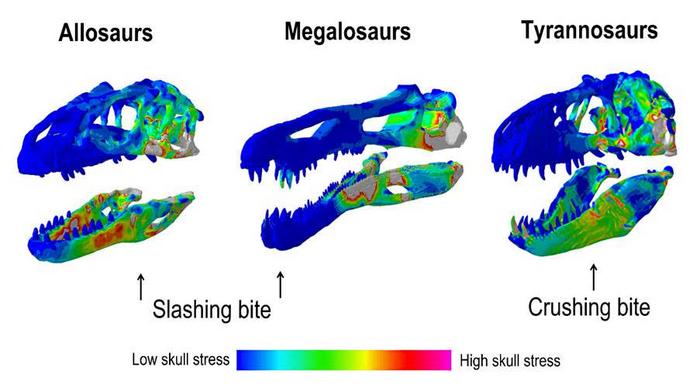

Researchers, including from the University of Bristol, found that while dinosaurs like the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex were optimised for quick, strong bites, much like a crocodile, many others that walked on two legs, such as the spinosaurus and allosaurs, had much weaker bite forces and instead specialised in slashing and ripping flesh.

The research, published in the journal Current Biology, revealed that meat-eating dinosaurs followed different evolutionary paths in terms of skull design and feeding style despite their similarly gigantic sizes.

“Tyrannosaurs evolved skulls built for strength and crushing bites while other lineages had comparatively weaker but more specialized skulls, suggesting a diversity of feeding strategies even at massive sizes,” Andrew Rowe, one author of the study from the University of Bristol, said.

“In other words, there wasn’t one ‘best’ skull design for being a predatory giant; several designs functioned perfectly well.”

In the study, scientists probed how walking on two legs influenced skull mechanics and feeding techniques in dinosaurs.

Previous research showed that despite reaching similar sizes, predatory dinosaurs evolved in very different parts of the world at various times and conditions and had different skull shapes.

This raised doubts on whether the skulls of these dinosaurs were functionally similar under the surface or if there were notable differences in their predatory lifestyles.

“Carnivorous dinosaurs took very different paths as they evolved into giants in terms of feeding biomechanics and possible behaviors,” Dr Rowe said.

To understand the relationship between body size and skull biomechanics, researchers used 3D X-ray scanning technology to analyse the skull mechanics and quantify the feeding performance and the bite strength across 18 species of two-legged carnivorous dinosaurs ranging from small ones to giants.

Researchers were surprised to find clear divergence among the species. For instance, skull stress didn’t show a pattern of increase with size.

Some smaller dinosaurs even experienced greater stress than the larger species due to increased muscle volume and bite force.

“Tyrannosaurids like T rex had skulls that were optimised for high bite forces at the cost of higher skull stress,” Dr Rowe noted. “But in some other giants like Giganotosaurus, we calculated stress patterns suggesting a relatively lighter bite. It drove home how evolution can produce multiple ‘solutions’ to life as a large, carnivorous biped.”

Overall, being a predatory two-legged dinosaur did not always equate to being a bone-crushing giant like T rex. Unlike T rex, some dinosaurs like spinosaurus and allosaurs became giants while maintaining weaker bites more suited to slashing at prey and stripping flesh.

“Large tyrannosaur skulls were instead optimised like modern crocodiles with high bite forces that crushed prey,” Dr Rowe explained. “I tend to compare Allosaurus to a modern Komodo dragon in terms of feeding style.”

“This biomechanical diversity suggests that dinosaur ecosystems supported a wider range of giant carnivore ecologies than we often assume,” he added.