Earth review — ‘Andor for Alien’

Two years before the Nostromo responds to that ill-fated distress call, another Weyland-Yutani vessel — with a lab full of extraterrestrial specimens — crash-lands on Earth.

Alien: Earth lulls you with familiarity. Opening on the clinical, white-padded walls of a Weyland-Yutani vessel, we find daisy-petal cryo tubes surrounded by glowing monitors that spit text with a furious chatter. A ramshackle crew, complete with creepy science officer and grousing mechanics, eat and smoke around the breakfast table. It’s an almost uncanny facsimile of Ridley Scott’s Alien, lifted straight from 1979. But while the USCSS Maginot (history nerds may knowingly smirk) is not the Nostromo, its mission ends just as unfortunately.

The crash (events leading up to which are saved for a later episode, one that could comfortably be described as the best Alien movie since 1986) brings us to an Earth thus far only teased at in Alien cinematic lore — one carved up and ruled not by governments, but by five mega-corporations. It’s into this supra-capitalist dystopia that the Maginot takes its nosedive, a familiar biomechanical monster stowed in the hold.

From a parasitic eyeball to vampire termites, every one of Alien: Earth‘s ornery ETs is concentrated nightmare fuel

The question of whether the Alien movie formula can sustain an eight episode series is answered early on — it doesn’t need to. Over five core films, two regrettable crossovers, and 46 years of cultural saturation, the Xenomorph isn’t the mystery it once was — something showrunner Noah Hawley knows all too well. Which is why the Xenomorph is just one of five specimens the Maginot has dredged up from the deepest reaches of space. From a parasitic eyeball to vampire termites, every one of these ornery ETs is concentrated nightmare fuel, with twisted life-cycles that provide a rich canvas for gnarly body horror — the zombie cat will live long in the memory, and you won’t look at either sheep or water bottles in quite the same way. Which is not to say that the Xenomorph itself is rendered obsolete — it’s deployed early, then withdrawn, Hawley making restrained yet effective use of Giger’s beast throughout the remaining episodes. Crucially, though, he positions the alien as neither antagonist nor narrative fulcrum, instead allowing its presence to serve as (admittedly deadly) scenery for a more compelling human story.

The city where the ship crashes is run by Prodigy, a corp just as unclouded by conscience, remorse or delusions of morality as the creature it covets. Its CEO, Boy Kavalier (Samuel Blenkin) — barefoot, perpetually pyjama-clad — is chasing immortality, transferring the minds of terminally ill tweens into synthetic bodies (adults are too inflexible, we’re told). It’s through these Lost Boys (and Girls) that the series explores the nature of consciousness, mortality, humanity, and what happens when the last is stripped away. These ‘Hybrids’ prove a compelling contradiction: their bodies adult, their mannerisms child-like, superhuman strength and speed giving each petulant tantrum an undercurrent of menace.

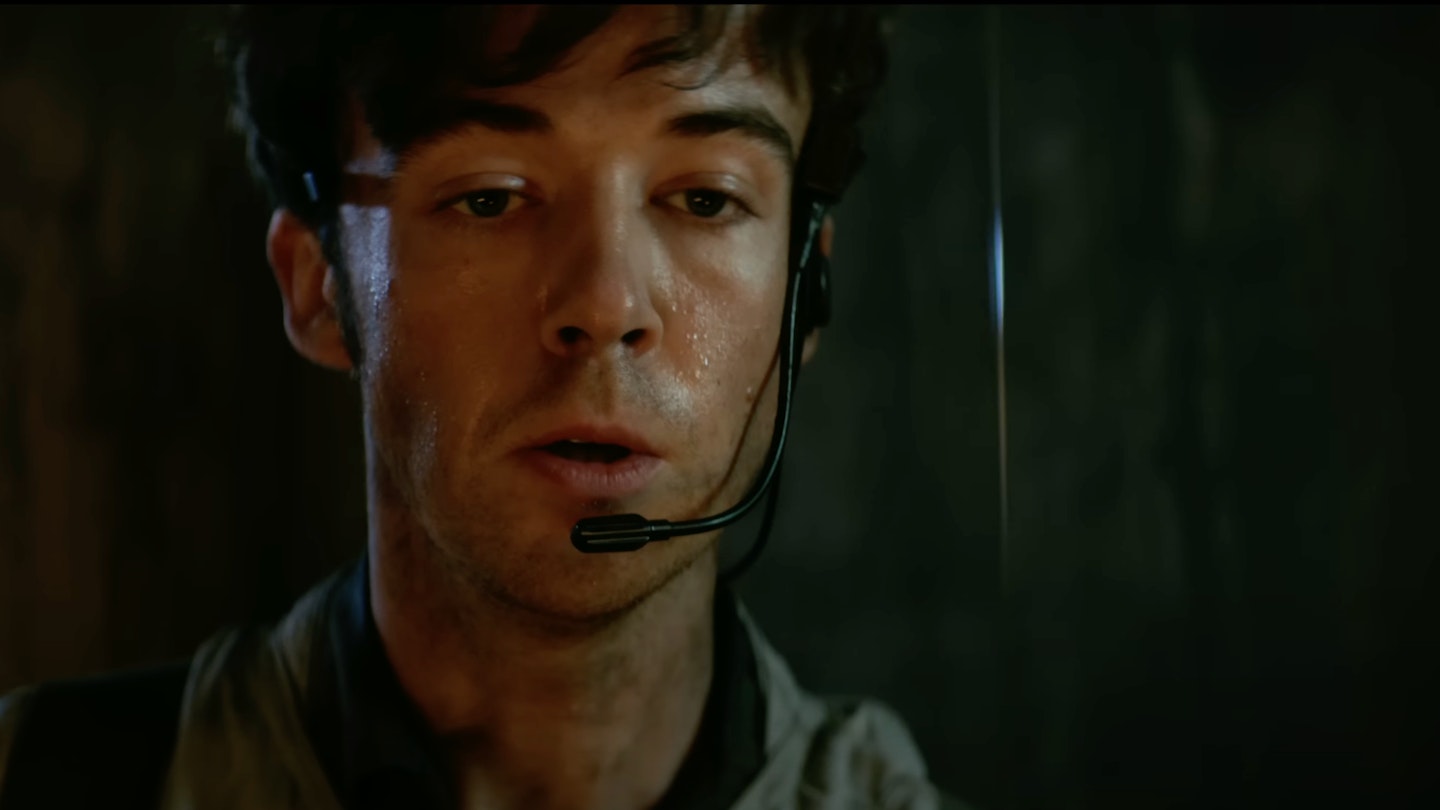

First among them is Sydney Chandler’s Wendy (the Peter Pan metaphor is anything but subtle), a mix of guileless naivety, wide-eyed wonder and flinty determinism — a hero owing as much to Newt as Ripley. Wendy’s connections to her human brother (Alex Lawther) and the Xenomorph itself (she begins to learn its language in a gambit that’s nowhere near as goofy as it sounds), combined with her dubious status as corporate property, leave her stranded between worlds. Meanwhile, Prodigy synthetic Kirsh (a snowy-haired Timothy Olyphant) has an uncertain agenda, and the Maginot’s sole survivor, cyborg Morrow (Babou Ceesay), quietly emerges as an antagonist every bit as menacing as the eponymous extraterrestrial.

After successfully cosplaying the Coens with Fargo, Hawley shape-shifts here from Scott (slow dissolves, measured dread) to Cameron (gung-ho Marines, crackling pulse rifles), channelling both classics that birthed this franchise, while simultaneously imprinting the show with his own distinctive mark (power-chord needle drops include everything from Metallica to Jane’s Addiction). Even the episode recaps are artfully crafted: discordant, vibe-based glimpses of key moments, rather than clumsy exposition.

The sum total of which is nothing short of a triumph. An Alien saga at once familiar and entirely fresh. An unsettling transhuman fable that stands on its own without aliens at all. An acutely cinematic experience, precision-tooled for hour-long instalments. If the drama’s edge is somewhat blunted by prequel armour (we’re under no illusion that a global infestation is imminent), and the nods to contemporary culture are occasionally jarring (a running gag from Ice Age 4 is unexpected), none of it detracts from the larger whole. Rather than lessen the Alien canon, events here succeed in casting the inciting events of both Alien and Aliens in a chilling new light. What could be higher praise than that?

Andor for Alien, Hawley’s series is a rare prequel that serves to enrich its source material, breathing new life into a once-tired franchise. This is the Alien resurrection we’ve long been waiting for.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/dolly-parton-Carl-Thomas-Dean-instagram-f8fab15643e44632a73ecf72b6456495.jpg?w=390&resize=390,220&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/bryce-dallas-howard-joaquin-phoenix-061825-2146197d386b40d1bcc1c6b27c4eaced.jpg?w=390&resize=390,220&ssl=1)